I don’t remember eating the way some of us look at our plates these days. We calculate whether we’re consuming enough calories, fibre, healthy fats, or protein.

A wave of protein consciousness has swept over many people on social media. Once seen as the fetish of bodybuilders, athletes, and the domain of nutritionists, protein talk is now on our phones. People measuring protein, worrying about carbohydrates, and remixing old food hearsays into new lifestyle scripts. For likes and shares, we like to believe. Meanwhile, fat, the old villain, must be feeling left out.

Protein talk is everywhere – self-care, ageing, beauty, performance, and identity politics. The age-old idea of food as medicine is being recast with protein being projected as the main character of energy.

Here in Mumbai, carbohydrates still reigns supreme. This is, after all, a port city that gave the world Vada Pav, Pav Bhaji, and Chinese Bhel. But as an island that grew out of fishing villages and salt pans, Mumbai has always been quietly rich in proteins too, in its many forms.

Also, protein in Mumbai and much of India has never been a neutral nutrient. Some of the most commonly used ones carry hesitation or stigma. Fish is considered too smelly, beef too controversial, and eggs are left out of mid-day meals. To eat, or to be seen eating, is never just about taste.

We have perfected a kind of food gaze: peering into the other’s plate and kitchen. And so, even in this new wave of protein-love, old judgments linger. A whey shake can signal aspiration, but a fried fish in a dabba can still draw suspicion.

To identify different types of protein in Mumbai, then, is more than just measuring nutrition; it’s to recognise the diversity here that makes this city a melting pot of food cultures.

In this photo essay, I do precisely what I critique: I watch what others eat. A quiet act of food surveillance, not to police or interfere, but to try and hold up a mirror.

Milk:

Milk has long held a special place in Mumbai, informal in the different panjrapols and tabelas and then organised in the last century as Aarey Milk Colony. Dairying shaped the city’s edge.

A shed in Aarey for buffalo that produce milk.

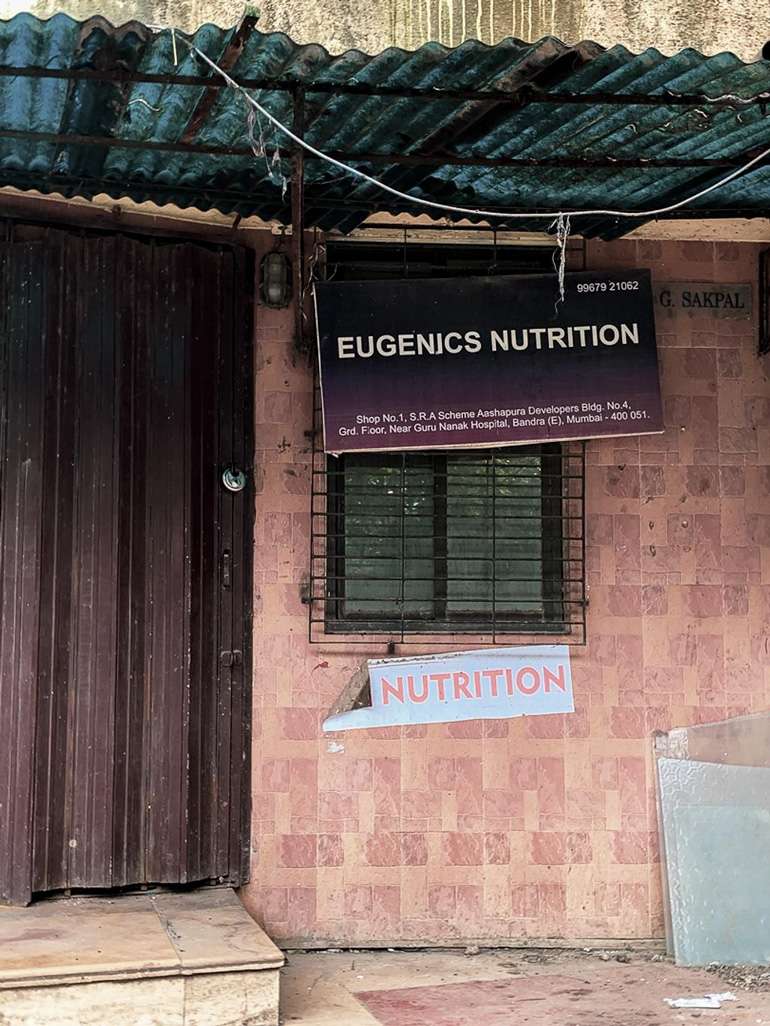

Outside Aarey, a stall from the organisation that sells milk and related products next to a shop that sells nutritional supplements – whey sourced from around the world.

Cows and buffaloes graze on the Deonar dumpyard that receives the city’s waste, completing the cycle of our waste becoming our milk source.

The Punjab and Sindh Dairy, a private dairy farm, collects vegetable waste from the Mulund market to feed its cattle at the farm.

Some consumers prefer the cow being milked in front of their homes.

A man who sells donkey milk door-to-door. It’s given to infants and very young children as a source of nutrition.

Fish Proteins:

Milk may be a popular choice in the city, but Mumbai has another ready source of proteins, thanks to the sea, mangroves, and the intertidal zone.

Pic 1: The heart of the city is home to several fishing hamlets and communities.

Pic 2: A crab from Chowpatty.

Pic 3: You can dig for a protein source in the intertidal zones and mangroves of Mumbai

Drying fish to preserve the proteins for the monsoons.

Drying Bombay Duck and Ribbon Fish on Madh beach.

A father takes his son out to learn about the tides, currents and fish in a Navi Mumbai fishing village.

A fisherwoman uses a board to move around the mudflats to harvest shells and crabs.

Fish for sale in the evening outside the Sewri Railway Station for people to shop on their way back from work.

A sample of what’s available at a typical fish seller who serves the working-class population.

Thousands of people work in the seafood industry in Mumbai. Much of their catch, and especially dried and preserved fish, is consumed within the city.

Freshwater Fish

Not all fish proteins in Mumbai come from the sea, they also come from other sources and from the other coast.

Traditional tools are used by the indigenous communities residing in Sanjay Gandhi National Park to catch fish in the streams and rivers.

The wholesale fresh water fish market in Dadar, where truckloads arrive from the Krishna and Godavari river deltas in Andhra Pradesh and the inland reservoirs in Maharashtra.

Freshwater fish sold on the streets of Shivajinagar, Mumbai.

The Chicken and Egg Situation.

What comes first? Chicken or egg?

In this story, let’s start with the egg because it is more commonly consumed, cheaper, and more readily available. Together, they are a more affordable and widely available source of protein.

Free-ranging chicken outside the Bandra Station.

A black Kadaknath rooster lords over his flock on SV Road in Andheri.

Plant Proteins

Despite all these sources, plant-based proteins are probably the most commonly consumed. The daily diet of grains and pulses keeps the city, like the rest of the country, going.

The discarded packaging of nutrition provided to children under various government schemes. Chana and Wheat.

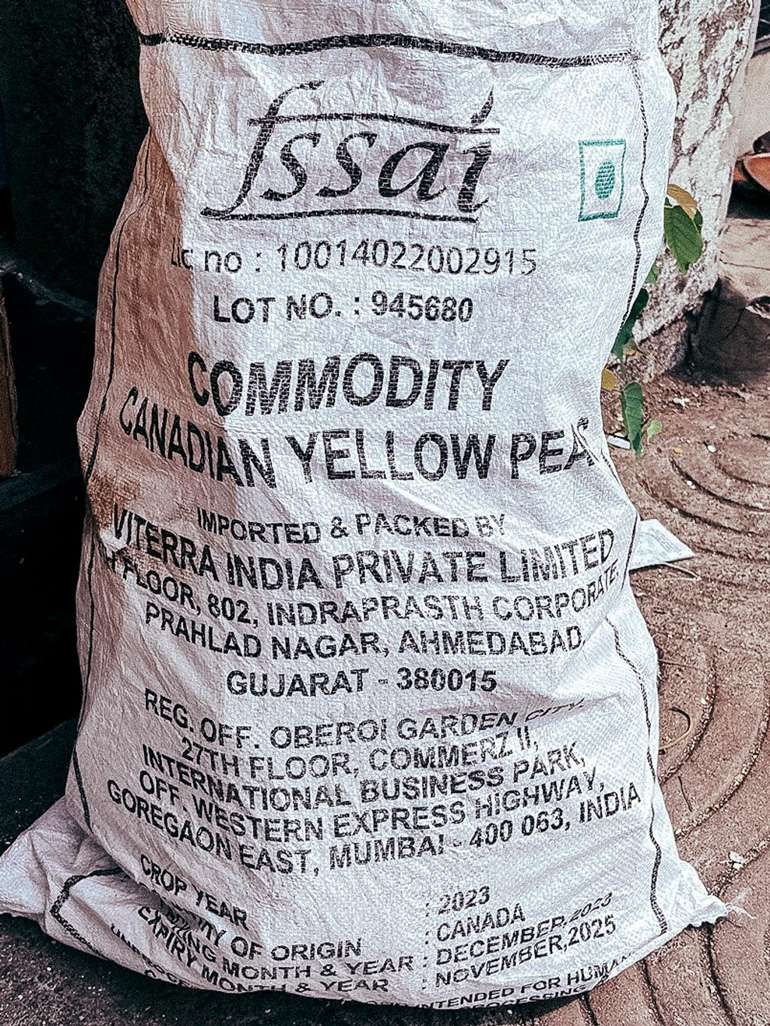

Packaging and labels provide clues about where the food consumed in the city comes from, such as Canada, via ports in Gujarat.

The government provided rice, dal, and a vegetable dish for workers at a metro site. A meal scheme for urban workers, which was initiated during the pandemic, has been recently discontinued. The protein sources included dal/pulses and grains.

Red Meat

The most prized and expensive protein in the city is mutton. A century ago, before poultry was industrialised, it was the main meat and the Sunday special in homes across various communities. Today, it’s chicken.

One of the largest melas or markets in Mumbai is the pre-Bakrid goat market at the city’s central abattoir in Deonar. Shepherds and traders from all over India, from Kashmir to Karnataka, come to Mumbai.

The numbers here show the number of sheep and goats that passed through the market this year before Bakrid

One of the roadside mutton stalls that is only open on Sunday mornings in Navi Mumbai. Senior citizens usually run them.

Food is one of the simplest pleasures we have, and protein is one of the most precious yet costly resources for the planet. Guessing and googling (or using AI now?) the origins of our food, tracing the ingredients on a plate, even in jest, is a way of paying attention to the world around us. To the city, to the people who feed it, and to the hidden networks that keep us alive.