Conviviality. A word derived from Latin word conviviere, meaning to live together and eat together. The word, which has come to mean friendliness, festivities, and pleasant sociability, assumes the presence of food. Eating, which is accompanied by people, and people who are accompanied by food on some happy occasion. (A funeral wouldn’t be called ‘convivial,’ would it?) What would then be the word for people who eat alone by force or by choice? Nonviviality, perhaps?

As I finish my solitary dinner at my rented flat near my workplace more than 100 kms away from home, I look back on my life and contemplate all the spaces and moments I have eaten alone, and with people. Growing up in a neither-joint-nor-nuclear family, we had somewhat strict meal times to be spent eating at the table with the family. On days when I had a holiday but my parents didn’t, my grandparents, especially my grandma, would make sure that I did not eat alone and that I concentrated solely on the act of eating. “Khete khete boi pore na, lokkhi saraswati r jhogra hoy,” (one shouldn’t read while eating, the goddesses Laxmi and Saraswati would start fighting) she would persistently tell me off to stop me from reading books while eating. I would hardly listen to her, as she would then go on to completely render her reproach defunct by saying, Amar baba o khub raag korto jokhon ami khete khete boi portam. (My father would also disapprove of my reading while eating). Most of my books had turmeric or oil stains on some of their pages, and sometimes crusts of dried food would emerge from within the lines of stories from books opened by an unsuspecting reader later. As I tried to fathom the meaning of her cautionary statement, I asked my mother why the two divine sisters, Lakshmi and Saraswati, would start arguing if I ate while reading. Forever the rationalist, she would reply, that’s just a way of saying, and the real reason is that you might choke on your food if you don’t concentrate on eating. But Ma did not tell me the implicit meaning: the Bengali belief that scholarship and wealth did not go hand in hand. Lakshmi is the goddess of prosperity, the material girl, and Saraswati was the goddess of knowledge and creativity, the scholar gypsy. “Lekhapora kore je, onahare more shey.”

Not onahaar per se, but ‘ekahaar’ definitely. Oh, I do not refer to the pious act of eating only once a day, which ‘ekahaar’ usually means. Ekahaari refers to people performing austerities, (or intermittent fasting?) but it could also, if twisted a little here and there, convey the idea of eating alone. This ek-ahaar, food for one, or eating alone, brings me to the Bangla word ekannoborti. Often used as a substitute for a joint family back in the day, ekannoborti roughly means the family that eats together, or rather, that cooks their rice (anno) in the same vessel and henshel—Bangla for ‘kitchen.’ A family that stayed in the same house but did not eat together meant that their handi (the vessel for cooking rice) had been separated. Separation of food definitely portended separation of property and soon a partition within the household, as seen in many 20th Century Bengali novels.

At school though, lunches were a minor distraction. ‘Tiffin time’ meant gobbling up whatever was given from home and running to the fields to play. It was also a moment of surprise, pleasant or unpleasant, each day as none of us knew what ‘delicacy’ was awaiting us in the colourful plastic boxes each day, maggicakes or cold ruti tarkari (roti sabzi) or paurutir halua, (a mish mash of vegetable leftovers and bread pieces cooked together, a dish probably invented by ma to kill two birds with one stone) unless the previous day’s delicious leftovers had been stuffed eagerly into them, creating serious anticipation and premature eating of the ‘tiffin’ before lunchtime. A slow eater, I used to exceed the allotted time of 30 minutes, and one of my teachers used to joke that I had to stop bringing ‘do tawla tiffin’ (two-storied lunchbox), referring to the dual levels of the box. Hunger scurried literally like rats, pet chuichui korche (stomachs squeaking like mice) and often classroom lectures would be interspersed with tiffin boxes being passed around and mouths stuffing under the desk and eating noiselessly and almost-chokingly to avoid being detected by the teacher. At other times, eating was merely a formality to avoid scolding at home (all of us are probably guilty of throwing away food we didn’t like, privileged little brats that we were) and rushing off to play Kabaddi or Kho Kho or lock-and-key and sweat in the hottest of afternoons. My younger sister, the innovator, would stuff food she did not want to eat in the unlikeliest of places. A bowl of dried, fungi-ridden Maggi noodles in the bookshelf that she had probably got bored of midway, hardened rotis under sofa cushions that our dog would discover one fine morning. But no matter what, we ate together at school. Someone’s good lunch would mean everyone’s good lunch; it did not matter if the bearer went hungry as long as everyone had a little bite of the previous day’s friedricechillchicken.

It was not the same during my Master’s. One would think that living and eating in hostels would be ‘convivial’, but neither the food nor the environment gave any occasion for joy or festivity. The hostel food was mostly bland, but there were days when I looked forward to the kadhi chawal or the fried rice and chilli paneer of Chandrabhaga hostel at JNU. The blandness of the hostel food at my sister’s school had led them to experiment with various degrees of chilli and spicy condiments with rice. It was she who introduced me to titaura, a Nepali dry aachar made of chilli and spices that tasted like gentle fire and childhood for its one-eye-closed, tongue-clicking tartness.

The mess where we had our meals in the hostels were huge diners which bustled with hostellers, and some of my friends from another hostel found it difficult to eat with strangers at the same table. I did not understand why they would feel conscious when people, especially men, were staring when they ate, something I was perhaps then indifferent to. They took the food back to their rooms and ate there, propping up the foldable tables to rest their plates and eat. I sometimes scoffed at their ‘hypersensitivity,’ and I remember saying how they had ‘internalized the male gaze.’ As I think back on their hesitation while at times enjoying the anonymity of solitary eating, I realize, there could also be something called forced conviviality. In a society which almost always forces you to do everything together, but at the same time alienates you whenever you express your wish to do something they don’t like, it could be distressing to force conviviality at a highly unequal table where men were gazing or ordering around or criticizing women who were mostly serving. Women students feeling conscious to go down and eat with their fellow hostellers was something I couldn’t understand perhaps because I felt safe in JNU, although, as my friend rightly pointed out, ‘the gaze is real’. Eating alone while watching Friends on the laptop in your hostel room would seem far more reassuring than hurriedly gulping food while some guy tries to chat you up at the dinner table down in the dining hall. Nonviviality has its own advantages.

Which I do not always feel as I clean up after my dinner, having paused a web series that I was in the middle of watching while eating. Reading while eating has now been unceremoniously dethroned by watching while eating, thanks to easily consumable content that kicks off the adrenaline much faster than books do, and does not demand undivided attention or focus. Making dinner after a long day’s work has consumed most of my energy, and the only thing left in me are the remnants of an attention that some thriller show on Netflix would not ask much of. Cooking for one is also an art. It never is the right amount. Too much, or too less, but mostly the former. Also, that existential question of what should I have for dinner? Yields to rising hunger pangs leading to the creation of the easiest, quickest one-pot meal that promises all nutrients. The answer is mostly a one-pot khichdi with vegetables and chicken or egg, and of course, achaar (pickle) to restore faith to the tastebuds. Ekahaar and ek achaar. Cāra in sanskrit is used as a suffix with other words: nishacār (nocturnal); jalacār (aquatic animals); sthalachār (land animals). Ekacār could mean a loner, but let’s just, for the sake of argument, say that it means one achar. And Ekacāri would mean being faithful to one achaar, having achaar once a day or having only one kind of achaar with the meal. If I had two kinds of achaar, would that be dwicārita (hypocritical), I wonder?

In Murakami’s novel 1Q84, Tengo, the protagonist lives and eats alone. The novel describes the process of cooking and eating alone in a quiet, organized manner that makes me question my post-cooking, post-apocalyptic kitchen and yellow-stained foldable little table for one after I’m done eating. I aspired for Tengo’s calmness and therapeutic cooking abilities, but realize I rarely cooked for myself in a calm way. The predominance of spices, especially holud (turmeric), in our cooking makes it impossible to stave off yellow or light-brown stains from utensils, tables and everywhere the food touches. Cooking for one, for me at least, was something I would have liked had I a well-equipped, well-stocked kitchen—luxuries that a temporary ‘home’ in a small rented apartment are hard to imagine. I did like it when I came home to Kolkata on weekends and days off. I had seen women cooking in films in plush kitchens while having wine, listening to music, and dancing. I tried the same, but was distracted by the music and the dancing and burnt my onions. There was also the anxiety that I especially felt when cooking for people. Cooking for myself on hellishly hot days evoked annoyance, impatience, and at times frustration; while cooking for others often induced anxiety. I wonder now if I even like cooking, or was merely pretending to like it because I am so impressed by the art of it. Cooking for one, like eating for one, is a concept that I have mixed feelings about, a sort of love-hate relationship that hangs in the balance.

I don’t remember since when I began romanticizing eating alone. Perhaps it was when I had time between two workplaces in the city, and had my breakfast after an early morning class or lunch after an afternoon of work at a nearby eatery. I was deeply aware of my privilege even then: I could never sit and eat at one of the bhaat-er hotels (cheap roadside eateries serving mostly lunch) like most working personnel at office-paras (commercial hubs) and more modest working-class spaces did, and I do not remember seeing women eat there alone, though men came, often unaccompanied, ate in a business-like manner, and went back to work. My husband often did the same when he began working, spending a measly 40 rupees for a satisfying meal complete with chutney and a piece of sweet. None of my women friends though, ever mentioned eating at such places, and preferred either the office canteens or the posher restaurants for lunch. Eating alone for a woman, I realize, is restricted to a class, and to spaces where women like me supposedly feel safe, and feel like a radical act has been committed merely by eating alone outside. While on the one hand, it reminds me of the closing scene of Margarita with a Straw, in which the protagonist eats in front of a mirror and smiles at herself, symbolizing self-love, on the other hand it makes me think of Manju pishi, our house-help who used to eat alone, sitting in a dark corner on the floor, once she had cleared our tables. Did she feel safe or conscious, eating in our house, I now wonder.

But almost everyone has a complex relationship with eating at least, if not cooking. In an article in The Atlantic, the author differentiates between ‘sad food’ and ‘solitude food’: the former being food that one eats while feeling emotionally distressed, upset and lacking in the company of others. ‘Solitude food’, on the other hand, is food that one gladly eats alone, enjoying and celebrating one’s company. As I put away the dishes after washing them, I wonder whether my dinner of dalia khichdi with chicken and vegetables and kool er achaar (Indian jujube pickle) today was sad food or cool enough to be solitude food. It was definitely easy food, I admit, and the word ‘easy’ conjures up images of wantonness in my mind. (Are wantons the best example of ‘easy’ food?) I indulge in sahajpak (easy cooking)—to go with sahaj path (Bangla for ‘easy read’, and also the name of a children’s textbook by Tagore) – and sahajiya bhojan, unlike sahajiya kirtan. And then I ask myself, can you really call yourself a cook if you mostly cook meals that are one-pot, convenience meals that serve to satiate your hunger and your taste somewhat on work nights, alone, while watching mouth-watering thrillers? My own company clearly isn’t enough for me to celebrate it when it is not in a posh cafe or restaurant, working on my laptop or reading a book with strangers eating at other tables, or at least facing a picturesque mountain at a distance in a hill station. An external stimulant is required to help forget the condition of loneliness. I have lost, or maybe I never had, the capacity to eat in silence. It is either the noise of the words or the noise of the moving images. So, was I ever ek-ahaari after all?

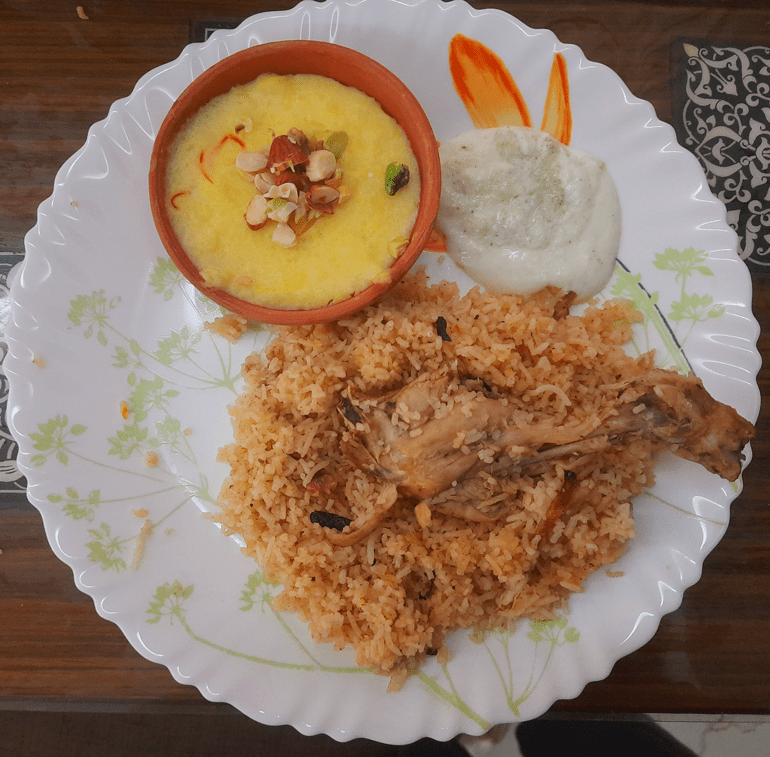

*Photos – Hiya Chatterjee

What a lovely read, Hiya! Very relatable in today’s life. Felt nostalgic reading about our school tiffin time and hostel mess and canteens later.

Thank you, Ankita!

Splendid

I have read the very nice story. I liked it. I think that some people by nature convivialent as well as some people unconvivialent.

Thank you!

I think it’s safe to say that this was some food for thought

Beautifully written, Hiya! It brought back so many fond childhood memories! I loved how you looked at some common bengali words from a different perspective and derived new meanings out of them. By the way, I took ‘ekahar’ to a whole new level by proudly eating ‘phuchka’ alone from the paarar’ phuchkawala’ in my college days. And though it might seem sad, I assure you, ‘phuchka’ being ‘phuchka’, it was always an increasingly satisfying experience! Ever tried that?

Interesting read. Eating alone is not something many Indians fancy, but it is becoming the norm now in the frenetic lives of today. Food for thought, definitely.

Hiya, I loved reading this! It took me back to those after-school afternoons when Ma and Baba were at work and I’d eat alone — my own little ek-ahaar moments. That’s probably when I started experimenting with food too.. You’ve written it so beautifully !!

In awe of how delicately this article has captured the ‘art’ of eating. One of the best reads of late.