Sha and Ja and Other Stories from the Silchar – Shillong Road

—Suranjana Choudhury

Volume 5 | Issue 3 [July 2025]

My first memory of being hungry is connected to a road journey. Many years ago, when our Shillong-bound bus had stopped somewhere between the hills and the valley, before any designated stop, something unfolded before me. Beyond the regular stoppages, these buses often indulged in unannounced intermissions. As it was an October afternoon, the unnamed place looked blueish green or greenish blue, the sky and the trees giving each other their colours. The place, our motionless state transport, sleepy passengers unaware of the halt and the overall sense of stillness seemed like a framed picture adorning someone’s drawing room. Through the bus window, there on the other side of the road, I saw a meal being cooked. A truck, which had covered many miles before and would perhaps do the same, was resting peacefully nearby. Overloaded trucks from different states of India carrying a motley of items fuming through the stretches of the northeast are easy to spot. An unhurried pace of an activity that looked more like a worship was underway; I took in the sight dedicatedly. A temporary kitchen was installed on the side of the road to serve the famished truck crew. Much later, I was told that this is a characteristic sight on long roads, which often serve as provisional homes to such trucks and buses. As they drive for hours together, cooking meals to have home-like food is a regular task. I was so used to expecting the kitchen as a permanently private space that I found this sight somewhat unusual.

My uncle, who had the sensibility of an ethnographer, got down and crossed the road; I followed him to see more. The most unexpected presence was a shil-nora on which lay a bunch of fiery red chillies, some cumin seeds and something else that I can no longer remember. One among the three or four men clustered there got busy grinding everything together. In a stainless-steel pot, I spotted sliced vegetables on a pool of water: potatoes, eggplants, and ridge gourd. A small bowl holding a few cloves of garlic and half-cut onions also lay on the ground. Within that circular space where the driver and his workmates were sitting, one could behold a Janata brand kerosene stove on which daal was being cooked, with little bubbles forming on its bright yellow layer. There was an unapologetic slowness about their cooking. Speeding on the road throughout the night and the early part of the day, here was the time for slow cooking and eating. The setup looked self-reliant. We stood like outsiders to the scene, a little unsure about how to converse with them. We’re supposed to talk to the truck driver about what it means to be a driver and a cook, then make a portrait in the words of both. They laughed and said something about their eternally moving lives. Cooking like this and having meals together made them happy. I thought they were very bold people, more than my cousin, who could climb the tallest mango trees to pluck mangoes for us. The one who cooks is bold. Now, when I think about this, I’m reminded of a poem by Imtiaz Dharker that I’ve taught my students a couple of times. Among many other things, the poem says:

On the Grand Trunk Road

thundering across Punjab to Amritsar,

this would be a dhaba

where the truck-drivers pull in,

swearing and sweating,

full of lust for real food,

just like home.

The truck driver and his team before us didn’t sweat or swear. They were simply content cooking a lovely lunch. Engulfed by everything around me, I felt hungry, and hunger, for the first time, felt nice.

*

Who, travelling between Silchar and Shillong, wouldn’t have known about the Mahamaya Hotel of Sonapur? Before Ladrymbai became the preferred destination of all the bus agencies, Mahamaya Hotel was the choice of the majority. I am not certain whether this change of location could be aligned with the many transformations concurrent with the immensity of the altered economic order. Sonapur was ‘the middle’ between Silchar and Shillong, if not arithmetically, at least in our imagination. Very prone to landslides during the monsoons, Sonapur anyway had our attention. If the buses were not delayed, they would arrive at the hotel around 12 noon. On top of a hillock, an untrustworthy sequence of steps leading one to its doorstep, the hotel always looked ancient. Right from the beginning, when I first saw it, everything about it – the walls, the manager’s counter, the windows, and the extended roof – looked old and tired, like old ancestral homes that never appear new.

I remember a particular afternoon. The hotel did not have a washbasin; water was stored in a plastic bucket with a similar tumbler floating on it. As I splashed some water on my face, every molecule of it felt like an alien on my summer-savvy skin. The cold was raw and fierce. However, the meal served in the hotel afterwards was warm and intimate. Familiar rice, daal, alu bhaja and a slice of lime had the potency of a dream. They also offered ‘shutki bhorta’ (cooked and mashed dry fish that is always spicy), which was desired by all. A few days ago, in my WhatsApp group with my childhood friends, when I asked them about the Sonapur hotel, all they remembered was the presence of Shutki bhorta, ’Shutki thakto, tai na?’ was the common response. I realised how, in our common past, shutki was a constant. It was almost impossible to conceive a complete meal without it. The hotel boys, as they were addressed, worked in a rhythm. Like performers in a musical or a play, they knew when to accelerate and how to slow down. They spelt out the subjects of the meal like a chant, without any pause or any sense of fatigue. In such hotels, no one has to wait for the meals to arrive. The smell of lunch wafting through the kitchen curtains would have to navigate the shortest route to reach us. Nothing seemed absent in the hotel. I liked its fullness and oldness. Outside, a stream was visible from a bamboo-made platform or something similar. My memory is inaccurate here. I wanted to sail a paper boat on that stream.

*

Sha and Ja. The two words sound like names of twins. Even though you don’t understand the meanings, you lean towards the rhythm. To my foreign ears, the words could mean anything under the sun. Since the signboard of a small shop bore the caption “Sha and Ja Dukan,” I guessed this implied some food items. It was during another travel, a car journey from Silchar to Guwahati. I hadn’t moved to Shillong yet, so everything about the hill station and its neighbouring places held excitement. We had already crossed major points, Sonapur, Ladrymbai, and Jowai. My travel companion wanted a tea break. Consequently, we started looking for a tea stall. We had the option of reaching Shillong to have tea and some snacks. But before that, this shop emerged before our eyes. Outside, the sun was ebbing slowly.

Sha and Ja – Khasi names for tea and rice.

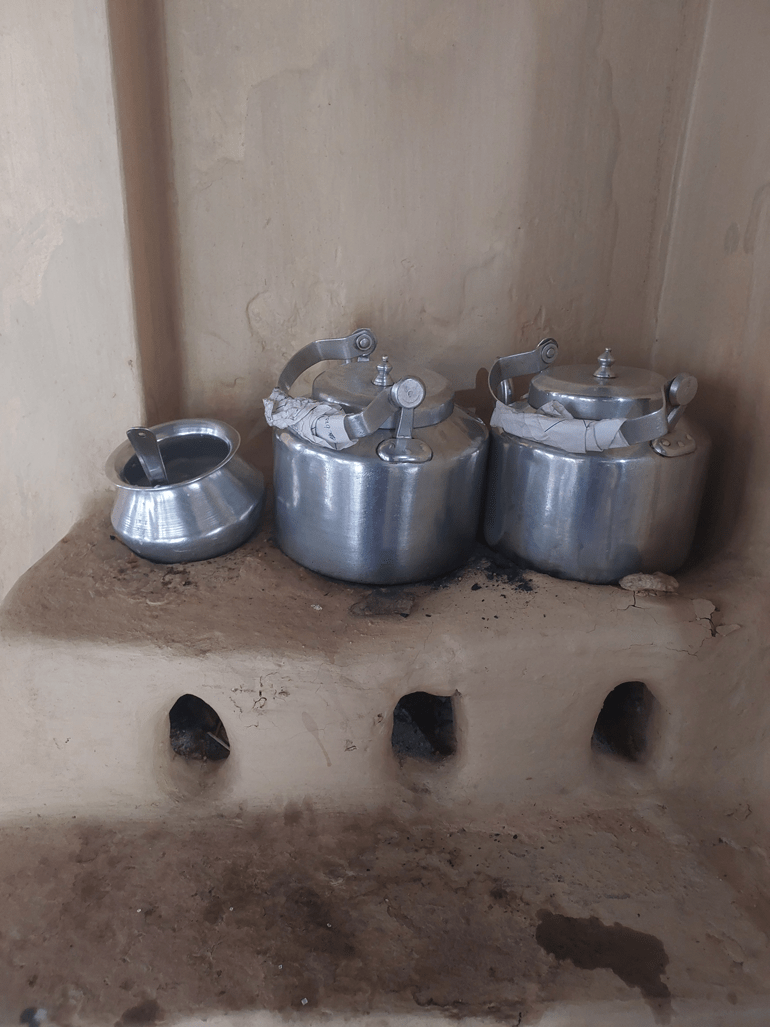

Like the hills around and patchy clouds above, the dimly lit shop looked like it belonged to the place. Not an outsider, but grounded and peaceful. Entering the shop, we ordered red tea (sha shaw). Sha-doodh is milk tea. An aluminium kettle settled on a stove, exhaling a trail of smoke, was worthy of attention because it looked like the cleanest vessel I had ever witnessed. A small basket containing a few food items was placed on one of the two benches beside a longish shelf in the room. Kubozo in The Book of Tea describes how the Japanese tea-room, on account of its freedom from vulgarity, serves as ‘a sanctuary from the vexations of the outer world.’ This tea shop, too, seemed to carry an inner world, the peripheries of which kept mingling with the rest. I am a compulsive rice eater, which prompted me to want to order rice. In response, the woman, the solo keeper of the shop, informed us that rice was unavailable.

A shop like this is referred to as Kong’s shop in Shillong, I know that now. Knowledge arrives with familiarity. Out of many popular tourist destinations in Meghalaya, I have visited Mawphlang Sacred Groves the most. Many astonishing views define this place. A puny tea shop is also a part of that encompassing view. It is quite easy to like whatever food – sha, ja, roti, chana, maggie, momo– this shop sells. On the map of my mind, the sacred forest, the vast landscape outside and the tea shop, in their separateness, seem connected in a curious way. One can find a sense of harmony settled in this connection. Like a good tea, this harmony settles on your body deliciously.

![Sha and Ja and Other Stories from the Silchar – Shillong Road <br>Volume 5 | Issue 3 [July 2025]](https://www.oneating.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/thumbnail-3.png)

Truly an engaging piece, ma’am. The way you weave food, memory, and travel into a single narrative is so evocative.

The bus journey from Shillong to Silchar or the other way round was so common in the olden days that as soon as there was the winter vacation of schools and colleges, lots would travel to the other side of the hills. The mid station Sonapur was the place to take the day meal. Summer time onwards was the marriage time and Silchar used to be the bride hunt destination in most of the cases.

But despite all these, nobody ever cared to bring the happenings into limelight before.

I appreciate your efforts to bring some obvious things of the olden days in black and white for the first time.

This is the first time I’m reading the poem.

Lust for food is a strong, powerful craving that can be difficult to ignore or control.