All eyes are on a big pot on an iron tripod over an open fire. When the lid rattles there is a collective gasp of admiration. Just then someone places a heavy stone on the lid and the rattling stops. ‘Go to sleep, move back.’ A mother’s voice or an aunt would try to shoo us away. At such times we held our breath. We hugged our knees up to our chins and stared at the fire. All eyes on the fire. If it died down, that stuff packed up to the brim in the pot would not cook. We were deeply immersed in the preparation of the Adi speciality called Etting.

One might call it a type of rice cake except that it is not round, or decorative in any way. It is a simple paste of rice powder and water heaped on to a shiny leaf, folded over with neat edges and pressed down into a rectangular packet, placed one over the other in a big pot for boiling. There is no filling – neither sweet nor savoury. Someone eating it for the first time would be hard put to comment on its flat shape and the bland taste, but to us it was the stuff of heaven. The anticipation was in opening the packet wrapped in the ekkam patta, the fabulous phrynium pubinerve, also called the packing leaf, seeing the leaf vein imprint on the spongy rice and inhaling its aroma.

One might call it a type of rice cake except that it is not round, or decorative in any way. It is a simple paste of rice powder and water heaped on to a shiny leaf, folded over with neat edges and pressed down into a rectangular packet, placed one over the other in a big pot for boiling. There is no filling – neither sweet nor savoury. Someone eating it for the first time would be hard put to comment on its flat shape and the bland taste, but to us it was the stuff of heaven. The anticipation was in opening the packet wrapped in the ekkam patta, the fabulous phrynium pubinerve, also called the packing leaf, seeing the leaf vein imprint on the spongy rice and inhaling its aroma.

Today, the making of etting has come a long way from when its preparation was a day-long exercise, when the rice was pounded by hand, and by the time the etting was wrapped and ready to cook, it would be night and ready to eat only the next morning. Etting is now easily available in roadside stalls. Travellers driving through the Siang valley can buy them in bundles of three or five packets. With a grinder in the kitchen, it is easy to make them at any time and making etting has become something of a commercial venture. Perhaps it has lost some its flavour along the way. With milled rice the etting turns out glassy in texture. In some homes it is modified with the addition of jaggery or coconut flakes, or a smear of achar, to spice it up a little. It does, however, remain a speciality food for auspicious occasions, prepared to celebrate a birth, weddings and festivals. It is also one item where the rice paste is placed on the smooth side of the leaf to prevent the rice from sticking when it is unwrapped. All other food, if they are to be packed, are placed on the underside of the leaf and packed with the shiny side facing outward. Food packed in reverse order is reserved for rituals and offerings for the dead.

Today, the making of etting has come a long way from when its preparation was a day-long exercise, when the rice was pounded by hand, and by the time the etting was wrapped and ready to cook, it would be night and ready to eat only the next morning. Etting is now easily available in roadside stalls. Travellers driving through the Siang valley can buy them in bundles of three or five packets. With a grinder in the kitchen, it is easy to make them at any time and making etting has become something of a commercial venture. Perhaps it has lost some its flavour along the way. With milled rice the etting turns out glassy in texture. In some homes it is modified with the addition of jaggery or coconut flakes, or a smear of achar, to spice it up a little. It does, however, remain a speciality food for auspicious occasions, prepared to celebrate a birth, weddings and festivals. It is also one item where the rice paste is placed on the smooth side of the leaf to prevent the rice from sticking when it is unwrapped. All other food, if they are to be packed, are placed on the underside of the leaf and packed with the shiny side facing outward. Food packed in reverse order is reserved for rituals and offerings for the dead.

But there are so many food preferences today. In Itanagar, Korean food tops the list. In my hometown Pasighat, there are grills and barbecues all along the road by the Siang River. Eating, for many of us, is not about seasonal fruits and vegetables anymore. Everything is available all year round. It is about master chef, multicuisine and fusion food. At the same time there is the constant talk about food security, about starvation and famine alongside the rhetoric of territorial waters and fishing rights – all the fruits of earth and sea gathered to satiate our appetites and then thrown away. One might well ponder the saying that having too much is the same as not having enough.

Etting is not lavish. Just rice and water cooked in the simplest way. Eat with happiness, our elders used to say. Take time to savour food. Rice was always on the menu. In Adi the word Apin, meaning rice, is equivalent to food. Rice is believed to be of divine origin and all the energy of a village used to be concentrated on growing rice. Originally it was the cultivation of highland varieties of the grain when forests had to be cleared and the land consecrated with prayers and offerings for a good harvest. A village would announce a day to make etting, and everyone would be happy, even though young girls would groan at the news because the arduous task of pounding and preparing rice powder would fall on them. The steaming packets of etting were shared amongst households as something special and auspicious. In modern times agriculture has shifted to wet rice cultivation (WRC) in the lowland areas, introduced in the state in the years following the India-China border war of 1962. Etting made with the hard-grained highland rice variety is a rarity now, but over the years etting has kept its speciality status whenever local cuisine is mentioned. It can be carried, stashed away in the fridge, reheated, or toasted over a fire. The edges will turn crisp and some people prefer eating it like this. It is easy to carry and it is biodegradable.

Perhaps it will enjoy a revival, who knows. Currently etting is a nondescript dish jostling against a feast of roast meats and exotic chutneys in culinary menus of the north-east region or Arunachal tribal food. Someday some entrepreneur might come up with a unique selling point claiming it as a pure product from ancient times, that it is made from the original paddy grown from the granary of mother earth herself who, according to Adi mythology, placed the precious grains of rice in the pockets of a dog’s ear who carried it back to man.

Making etting at home is still a bit of an occasion and a collective effort, just like in the old days. Despite modern gadgets in urban kitchens today making it easy to have rice flour on hand, I find it’s more pleasurable to make etting when it’s a full house with nieces and nephews and cousins and relatives around. First, the ekkam patta has to be collected. Its growing there – in the garden, but this leaf likes dark, shady spots, prime location for slugs and bugs, and its collection is better left to someone other than me. Then there is the consistency of the rice paste to be considered. How much water? Too much and the dough will be runny. Too little and the stuff might turn out all lumpy and hard. We can use different mixtures of rice – sticky Pasighat rice, red rice, plain white, or a mixture of both. Then there is the pressure of my hand as I put a dollop of the mixture in the centre of the ekkam patta and fold the leaf over, lengthwise, with a neat pleat down the middle and press down and to spread the dough – too hard and the dough will spill out before I can fold over the top and bottom half to make everything into a packet with one end tucked into the fold of the other. A big leaf is placed at the bottom of the pot before the rice packets are packed in with another leaf tucked in over the top and the pot filled with water, lid on, and set to boil. There. Done. When the lid rattles, I still use a flat stone to hold it down. The etting is ready when the dough can be pulled off easily from the leaf. For this there’s no easy way like throwing spaghetti on to the wall to see if it sticks and know it’s done; for etting someone has to take out a packet, and, when its open, everyone can taste it and say give it another five minutes, the ones in the centre may be a bit chewy or, it’s done, its perfect! Cooking time is about an hour. There is also a cooling period when the etting is taken out and placed on a tray to let excess water drip out from the folds of the leaf.

A fair sample of the diversity of Arunachal food can be experienced during traditional festivals of which there is one almost every month of the year. At one time the Indira Gandhi Park in the capital used to be a hub of activity with food, music, books, and concerts during the statehood day celebrations. It was an open event, an exhibition of local food, food grain, ginger, pulses, fruit, fish and medicinal herbs with cooks and experts from different parts of the state giving live demonstrations of a variety of food preparations from making momo and thukpa to dishing out sausages and shabaley meat pasties from Tawang and Menchuka to cooking with bamboo shoot and pikey pila in central and eastern Arunachal. It was where I first learnt about paasaa, a famous cold fish soup of the Khampti community, and the famous bamboo rice called khau-laam.

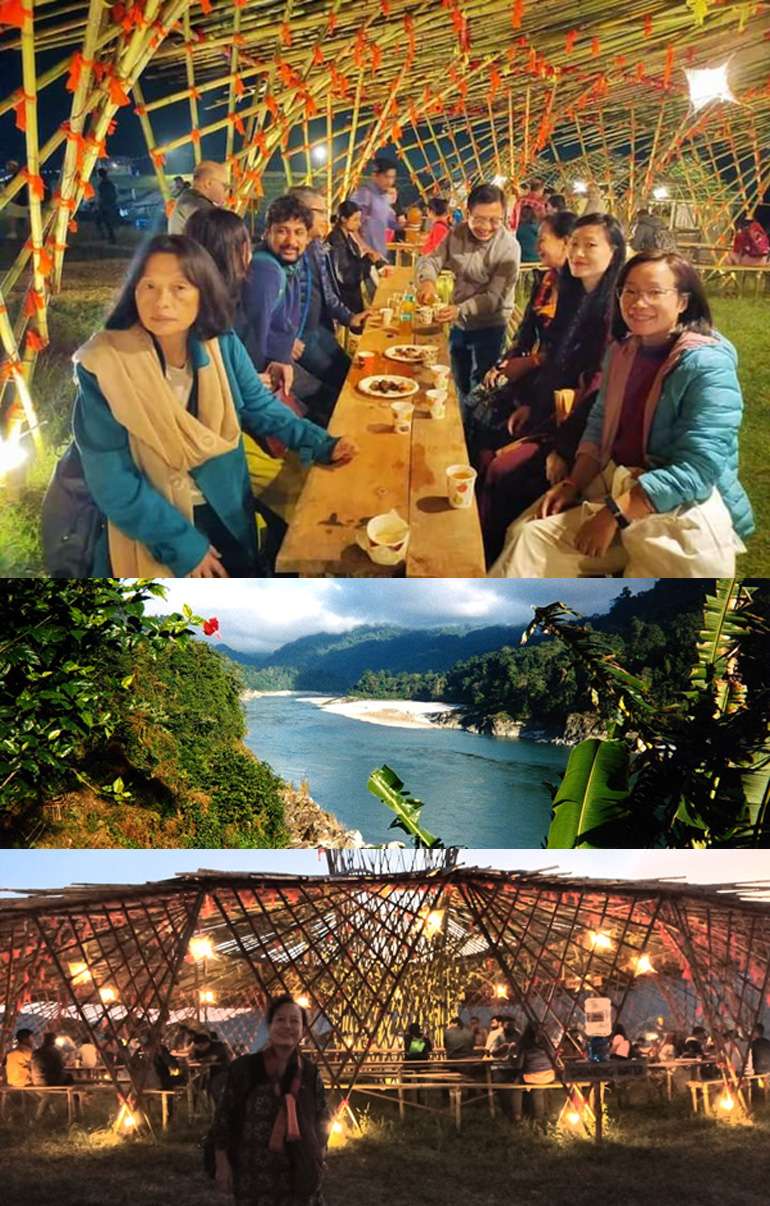

For khaulam, rice is soaked overnight and then filled into bamboo tubes with just enough water to cook the rice while allowing enough space for expansion during cooking. The tubes are sealed with a piece of the ekkam leaf and placed on an open fire. The bamboo used is a variety known locally as khaulam-ba, a soft bamboo with a thin inner membrane that wraps around the rice sealing in its full flavour and allowing it to be removed easily in one cylindrical piece once it is done. The preparation of bamboo rice requires a great deal of attention to ensure that the rice is thoroughly cooked and not burnt. Once ready the rice can be eaten by simply pulling back the soft bamboo or cutting the bamboo into clean pieces. It is a great favourite for visitors and though the food festival, as it were, during statehood day has been discontinued, the first pioneering efforts to showcase local food and woo tourists to the state has continued in the avatar of new eateries and tribal food joints serving khaulam and a variety of traditional rice preparations like sticky rice roll, chicken stew with broken rice gravy, and plain steamed rice wrapped in the versatile ekkam patta called pinpu. Local food stalls are also the hallmark of modern-day festivals drawing large crowds and long queues at the annual Ziro Music Festival and the Orange Festival of Adventure and Music at Dambuk, to name a few.

Food, memory, music, change… in the evolving scenario of changing food preferences and habits there remains one other well-known local speciality that has weathered time and change. Rice beer. All Arunachal communities make this alcoholic beverage, calling it by different names, though in common parlance the Adi word apong is the one recognised by visitors and different communities alike. Apong is pan-Arunachal.

I once got it into my head to try and make apong. The chief ingredient for apong is rice and I worked hard cooking a large quantity of rice. It was hot, arduous work especially as I was aiming for the black rice beer that we call ennog, which is quite different from the milky white, pressed apong. For black apong the recipe demands the addition of burnt paddy husk for filtration, and the rice has to be stone cold before yeast is added to it, otherwise the apong might turn sour. My sisters and I had the paddy husk ready, after more hot work of procuring sacks of it from a rice mill in Assam. It was all fuss and clutter in the kitchen. The next step was to spread the cooked rice on a bamboo mat to cool. The instructions for making apong were clear, but I think intuition also plays a part here and one has to be sensitive to touch and feel, to the texture of the rice and the fermenting agent called siye crumbling into it. The origins of this yeast and how it is prepared is a bit of a mystery. Apong veterans tell me the first siye appeared at the same time as the first man on earth. In the market it is available as dry, white discs varying in size from a small biscuit to a flat, larger pancake. Too little of it and the rice might stay inert. Too much siye and the mixture might turn bitter. Every apong brewer has their favourite siye supplier, or secret recipe for it, keeping a bit of the old biscuit, a bit like sourdough starter, to make more of their own. The final step is to pack the rice mixture into big baskets and let the siye work its magic undisturbed.

Black apong is a speciality of the Siang valley and in villages it is still made on a daily basis. My sisters tell me it is a back-breaking chore but they have the rice and the paddy, and they have the skill and knowledge to make the best apong in the world. After my rather futile attempt at home brewing, we buy the readymade apong mixture packed in baskets, to distill at home. Apong is also sold in bottles, but unlike wine apong does not improve with age. Perhaps it will enjoy a new glory, enjoy a longer shelf life with modern technology and preservation methods. For now, it is served fresh as soon as there is a full jug to pass around. Aficionados say there is no need to find out how long it will keep. It is enough to sit together surrounded by tall mountains and rivers, and raise a glass to celebrate all the good things, for the invention of apong is a gift that makes men equal to the gods.

Love the way you explained it like a professional cook. Cooked red rice of Monpas is also a favourite of mine. Thanks for the article.

Nice reading. Your way of expression itself added extra flavour.

Great reading!