Leftovers and Loneliness

—Iftikar Ahmed

Volume 5 | Issue 2 [June 2025]

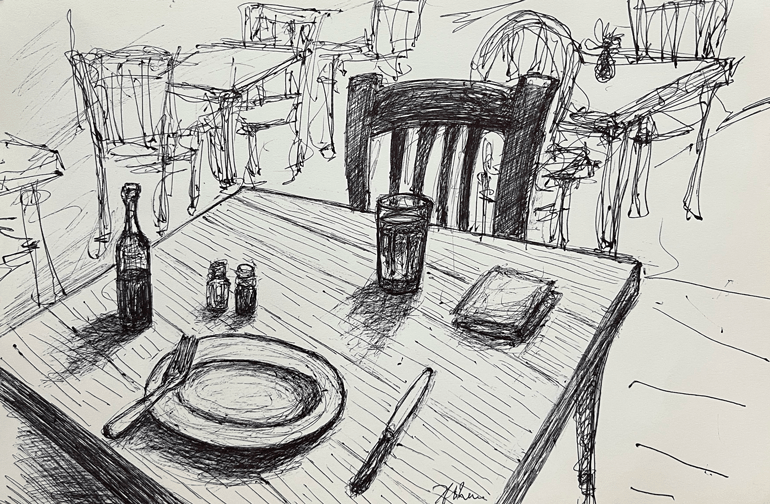

A Seat Across That Was Never Taken | Art: Iftikar Ahmed

It begins, as quiet undoings often do, with the refrigerator light. Not the grand drama of hunger, but the soft, humming glow of indecision. 2:14 a.m., and the fridge is a theatre: steel tiffins stacked like scenes, half a bowl of dal looking up like it has something left to say. There’s the leftover sabzi, now stiff with time; a single roti folded like a note no one read. I stand there barefoot, deciding whether I’m hungry or simply lonely. At that hour, they’re often indistinguishable.

I don’t bother plating it. The microwave gets two minutes. The roti is sprinkled with water, softening like someone reluctantly returning to a conversation. I eat over the sink—not out of shame, not exactly—but because a plate feels like a commitment. Or maybe because shame, when it becomes habit, learns to disguise itself as convenience.

Eating alone isn’t sad at first. It’s a matter of logistics. Then it becomes routine. Then it becomes a ritual you don’t remember creating. Nobody asks you what you feel like eating, so you stop asking yourself. You reach for what’s left. You call it dinner. You chew on silence.

And yet, there are days I love it. Eating alone means no pretence. I lick my fingers. I mix rice and sabzi with my hands. I use too much achar. I don’t wait for anyone to finish before starting. There’s a freedom in that. But even freedom aches when it goes unwitnessed. Even joy, if not seen, begins to fade like spices left uncapped too long.

What we call leftovers are not just food. They are memory, congealed. Time made chewable. The day’s edible sediment. A forgotten pinch of ajwain reminds me of my grandmother, who used to say, “Eat the last bit. It remembers more.” I thought she meant taste. Now I know she meant grief.

We often think of eating as a social act, but solitary eating has its own grammar—more fragmented, more tactile. It’s not the table, but the fridge door that becomes the site of decision. It’s not conversation, but heat and smell that guide you. It’s not plating—it’s proximity. What’s near, what can be reheated, what feels bearable.

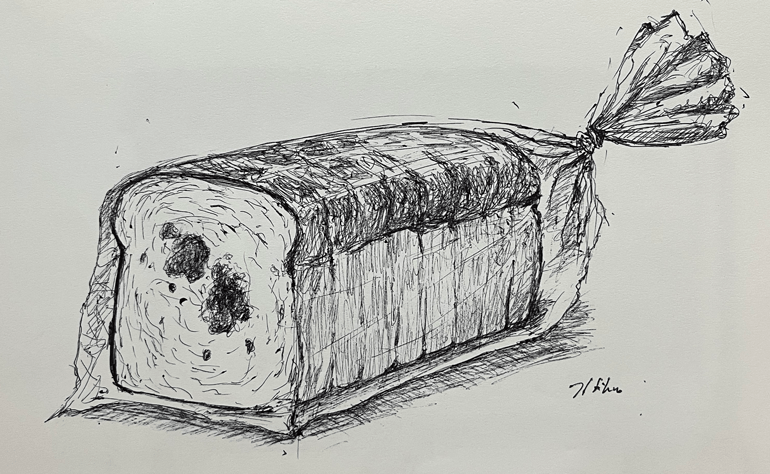

Cold Storage | Art: Iftikar Ahmed

In cities like Delhi and Mumbai, where the language of food is productivity—smoothies, diets, meal plans—leftovers are a kind of rebellion. They are not “fresh,” not aesthetic. They come with no garnish. They arrive with no caption. They sit in the back, quietly enduring. To eat them is to refuse the tyranny of the new.

A friend once said, “Leftovers taste like what no one wanted.” But I think they taste like survival. They are the part of the meal that wasn’t consumed by the performance. They are what stayed when everyone left.

This isn’t a romantic essay about solitude. It’s about the texture of it. Solitude, when prolonged, doesn’t become profound—it becomes procedural. You learn the timings of your microwave. You learn which container leaks. You learn that your appetite is as moody as your memory. You begin to eat not when you are hungry, but when you can no longer avoid yourself.

Leftovers are intimate. They know the hands that made them. They’ve already been warmed once, softened by another fire. They arrive without expectation. You don’t need to impress them. You only need to show up.

And maybe that’s what makes them feel like truth.

There’s a specific kind of attention reserved for those who eat alone in public. It’s not always cruel—often it’s curiosity, sometimes mild pity—but it is rarely absent. A solitary diner is seen as either pitiable or suspicious. Especially when the solitary diner is a woman. The assumption is: she’s early, she’s waiting, she’s been stood up. A woman eating alone, without apology or distraction, confuses the room. It shouldn’t. But it does.

A friend once told me she never finishes her meal when eating alone at a restaurant. “If you leave something on the plate,” she said, “it feels less final. Like you might still be waiting for someone.” There’s a quiet performance even in absence—small gestures that try to keep aloneness from looking like abandonment.

Men aren’t exempt either, though the expectations shift. A man eating alone may be invisible, or assumed to be working. There’s less cultural suspicion, but also less care. Solitary male eating is often seen as the default. But default is not the same as peace.

For me, the restaurant table has always been a stage I’m not quite sure I belong to. There’s a self-consciousness in placing the order, in how long you take to read the menu. Even in pretending to scroll your phone, you are performing an audience. Because God forbid someone thinks you’re present—with no purpose.

At home, the rituals change. The performance softens. You begin to cook not just to eat, but to remain in contact with time, with self, with memory. You learn to make smaller portions, you learn to fold a single roti like it matters. You get creative. Half a tomato. A splash of milk. Improvisation becomes intimacy. And leftovers, always, return—like letters sent back unopened.

But eating alone isn’t just about loneliness. It’s also about control. A quiet, nonviolent form of it. You decide the spice, the portion, the silence. You don’t need to explain your cravings. You don’t need to justify a meal made entirely of mashed potatoes and pickle. Taste, unmediated, becomes its own companionship.

Still, there are moments when even that freedom curdles. A few winters ago, I made myself chicken curry late at night, only to realise halfway through that I was replicating a meal once cooked for someone else. Everything—the proportion of onion, the splash of vinegar, the way I cut the coriander—felt like choreography I no longer believed in. I stopped eating. I put the lid back on. I didn’t open that dabba for four days.

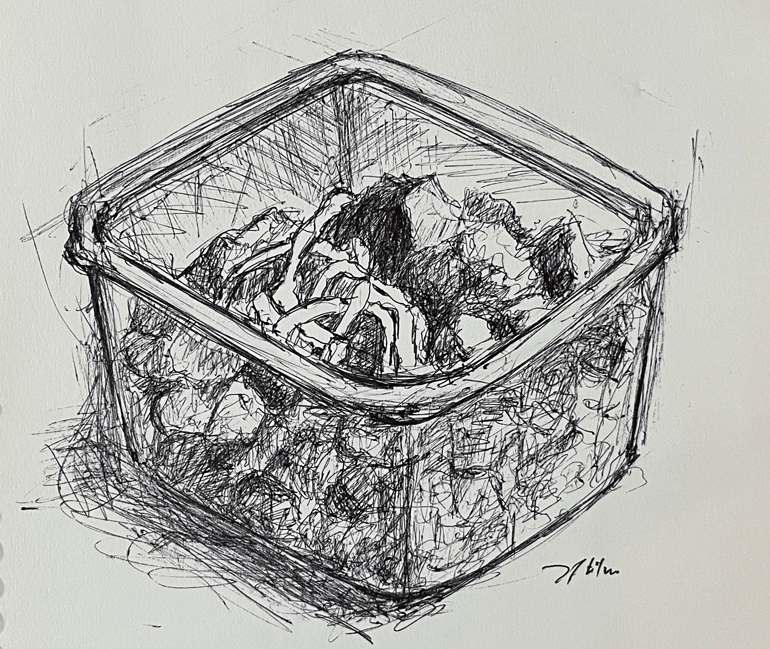

Still Moulding | Art: Iftikar Ahmed

When I finally did, it had turned sour. I wasn’t surprised.

That’s the thing with leftovers. They keep the memory of who you were when you made them. And sometimes, that’s harder to digest than the food itself.

But there are also days when they save you. A bowl of khichdi left from the night before. A forgotten bit of rajma in the freezer. You come home, exhausted, speechless—and it’s there. Not demanding. Not fresh. But present. And sometimes, presence is enough.

There’s a joy, too. And not the Instagrammable kind. The kind that comes from eating exactly what you want, with your legs folded on the couch, watching the same film for the fifth time. The kind that comes from cold pizza for breakfast, or buttered rice with nothing else. Joy that isn’t photogenic, but feels like a room exhaling.

This is the emotional texture of solitary eating—it’s not just about absence. It’s about the small ways we hold ourselves, the soft negotiations we make with memory, and the unexpected defiance of continuing to care for a body that no longer has anyone to impress.

I’ve always been drawn to the aesthetic of solitary meals—the quiet visual grammar of reheated dal in a steel katori, rice scooped into a chipped bowl, a spoon left tilted in a teacup like punctuation. These meals aren’t composed for beauty, but beauty often leaks in. Not curated, but accidental—like rain making a pattern on a window. There’s something poetic in the clumsiness of it.

One spoon, one plate, a folded napkin you don’t end up using. No garnishes. No symmetry. Just food and its fatigue. And yet, these are the meals that feel most honest to me. They don’t sell anything. They don’t ask for approval. They’re not designed to be witnessed. They just are.

But to speak of food without speaking of caste is to miss the real sediment. In many upper-caste Hindu households, leftovers—baasi khana—are treated as impure. Food is made fresh, offered to gods, served with rules of proximity and purity. Leftovers are often unspoken, even when consumed. In contrast, in working-class and Dalit homes, leftovers are necessity, strategy, and sometimes celebration. A pot of rice is deliberately made in excess. A curry is designed to taste better the next day.

The leftover, then, is not merely what remains—it is also what some are forced to live on. The question of who gets to eat “fresh” and who eats what’s left is not just about taste. It’s about hierarchy, access, and ritualised denial.

Growing up, I remember how food was divided at home. There was “guest food,” plated with care and ghee; and “daily food,” practical, plain, reheated. No one said it out loud, but it was understood: some food is for display, some for endurance. We internalise this early—the idea that some hungers are worth feeding immediately, and others can wait. Sometimes for hours. Sometimes for generations.

There’s a strange intimacy in eating what others won’t. It feels like an act of reclamation. Or maybe just stubbornness. A kind of loyalty to the neglected.

Once, during a particularly grim stretch of days, I survived for a week on variations of the same meal: toast with fried eggs and pickles. Breakfast, lunch, dinner. One night, I got experimental—added ketchup and oregano. It was horrible. I ate it anyway. It wasn’t about taste. It was about continuity. About proving that I could still assemble something. That I could still feed myself, even if I had lost the appetite for conversation.

Taste, after all, isn’t just on the tongue. It’s in the hands. The decisions. The patience. The timing. The willingness to let something rest before returning to it. Taste, when unobserved, becomes a deeply private language. You start to understand what you want not by craving, but by noticing what you reach for.

I’ve thrown away food not because it went bad, but because it brought back something I couldn’t swallow—an evening, a face, a phone call. A smell that felt like someone else’s memory. These are the leftovers no one talks about. The ones we bury in napkins, rinse down drains, cover with air freshener. They rot quietly. And we let them.

But on most days, leftovers feel like a form of self-trust. A quiet signal that I believed I would be hungry again. That I believed I’d still be here tomorrow, opening the same fridge, choosing warmth over nothing.

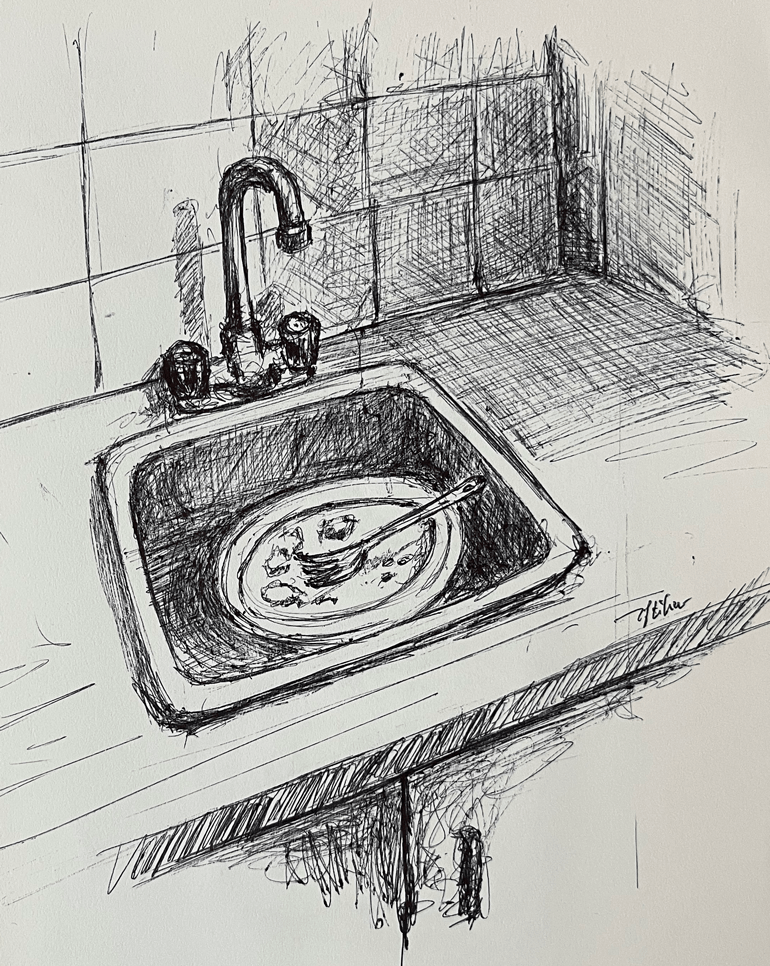

The Box of What Wasn’t Finished| Art: Iftikar Ahmed

There’s power in that belief. A subtle, stubborn refusal to disappear.

What remains is not always what was forgotten. Sometimes, it’s what we deliberately kept—half a bowl of sabzi, a slice of cake, a single spoon of kheer left in its glass bowl like a promise. We don’t always save food because we’re frugal. Sometimes we save it because we’re not yet ready to say goodbye.

Leftovers are not just remnants. They are future intentions. They are the part of the meal you believe your tomorrow self will have the appetite to love.

When I open the fridge and find something I made days ago, something softened and quiet, I don’t always feel shame. I often feel recognition. That yes, this too is a part of me: slow, stored, still waiting to be warmed. Not wasted. Just paused.

I remember my father, years ago, returning late from work. He would eat alone at the dining table long after we’d gone to sleep. No noise, no fuss. Just a reheated plate and the soft clink of steel. I never thought of it then as solitude. But now I realise—he was keeping something going. Not out of hunger, necessarily, but out of rhythm. The food, the plate, the act—these were anchors. When everything else frayed, they held.

Maybe that’s what leftovers offer: a small form of continuity in lives that are otherwise too fragmented to hold together. A gesture of care that says, “You matter tomorrow too.”

There are days I cook something just to store it. I don’t eat it immediately. I want to see it waiting.

Aftertaste | Art: Iftikar Ahmed

for me later—on a tough afternoon, a lonely night, a day when the world is too loud. That act feels like sending a letter to myself across time. A jar of dal. A folded roti. A quiet reassurance: you’ll want comfort again. And here it is.

This isn’t to say solitary eating is always tender. Sometimes it’s brutal. You eat whatever is left standing. You microwave too fast, burn your tongue, and eat standing in the kitchen like you don’t deserve to sit. You chew too quickly. You don’t taste anything. These meals, too, have their truth.

But what I’ve come to love is how solitary eating teaches you to stop performing taste and start listening to it. You learn to honour strange cravings. You make peace with uneven portions. You realise that sometimes, comfort looks like buttered rice and pickle. And sometimes, it looks like skipping dinner altogether and calling it a fast you never meant to keep.

There’s an emotional politics to eating alone. It asks: when no one is watching, how do you nourish yourself? What do you consider worth saving? What do you discard too soon? What does your hunger actually want?

Lately, I’ve been thinking that perhaps the most intimate act is not cooking for someone, but cooking for no one—and still making it taste good. To say: I may be alone tonight, but I am still worth the effort of mustard seeds, of good rice, of heating oil till it hisses.

There’s a bowl of overcooked khichdi in my fridge right now. The grains have dissolved into one another, tired but holding. I don’t know when I’ll eat it. Maybe I won’t. Maybe I just needed to make it, to remind myself that care can be quiet and non-linear. That not everything made must be consumed. Some things exist simply to be tended to.

And that is enough.

Leftovers are not shame. They are survival. They are patience. They are the soft underside of ritual. They ask for nothing but return.

Not hot. Not dramatic. Just warm enough to hold you till the next meal.

So poignantly captured, every sentence, the structure, the feeling seems to be dancing with grief, isolation, loneliness yet poignancy. Loved the article, especially the moving imagery it created in my head while reading it.

Lovely read!

So well written. And so very relatable. Reminded me of so much I’ve done over the years and still do.