It was a time when Showaddywaddy, the rock & roll revival band, was topping the pop music charts. I was the proud owner of their LP record and the hit single “Under the Moon of Love” had craftily manoeuvred itself into the core of my being even as the periodic brick would crash through a window pane of our modest semi-detached house in Seacroft Hospital in the eastern part of the city of Leeds. It was the late 1970s. The infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech by the Conservative British MP Enoch Powell was still fresh in the minds of migrants and street thugs alike. Working class neighbourhoods in the north of England seemed to be perpetually on the edge. The shattered windows were replaced, complaints filed, and life returned to primary school and pop songs for me, from the little I recall.

Amidst all this, as migrants are apt to do, my mother sought to recreate the flavours of the homeland. Its ameliorating effect cannot be understated. A powerful and often mystical sensory transportation melts away the distance of continents, and momentarily suspends the bitter cold, unsure future, and racial tensions. In our Andhra household, with its struggles to find suitable Indian groceries alongside sensible clothes and functional accents, it was the ubiquitous duo of ooragai (preserved pickle) and pachadi (fresh chutney) that sat at the centre of the dinner table. While the former was carried in sealed jars from distant Hyderabad, the latter had to be recreated. Starved of appropriate ingredients, my mother devised a pachadi from cooking apples, perhaps using the famed Bramleys. Peeled, shredded and blended with a tempering of fenugreek seeds, mustard seeds, chillies red and green, a smattering of split urad dal, a smidgeon of asafoetida, some judiciously spooned in salt (and sugar), and of course, the mercurial agent provocateur—the dark, delicious mass of tamarind pulp. Or a surrogate squirt of a lemon. If anything, the colourful, aromatic, spicy, and tart culinary centrepiece happily corralled memory, belonging, and comfort into a flavourful embrace.

More recently, at my aunt’s kitchen garden in suburban Baltimore, I helped harvest her lovingly cultivated late summer crop of gongura—Asian Sour Leaf or Roselle. A consignment was to be transported to a cousin in upstate New York. The prominent ambassador of Andhra cuisine gongura pachadi, with its spicy-sour credentials, is commonly found in homes and eateries alike. Not to mention wedding feasts. Much like my mother, my aunt too had her own innovation—cranberry pachadi. Common to these trans-continental culinary conceits is the much-loved lip-puckering taste note of Andhra & Telangana, and arguably of South-Central and South India. Pulupu, khatta, or sourness is the dominant flavour across these regions, distinguishing the land and its people from northerners and their humdrum ignorance and derision of South Indian peoples and their complex cultures.

As the historian and epigraphist S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar reveals in his seminal History of Tirupati, Tamil and Sanskrit literary sources mention Vengadam, the traditional name of Tirupati. Located to the north of Tamil land, beyond it lived the vaduku, or Telugu people (in this case). The boundaries of Tamil country referred to in the Tolkappiyam, the ancient classical grammar of Tamil, Aiyangar adds, lie between Vengadam in the north and Southern Comorin (Kumari) in the south. Very interestingly, he further reveals that the Sangam period Tamil poet Mamunalar in Poem 311, “refers to the good country of Pulli [a regional chieftain], and the desert past it, and describes the feature that the people were accustomed to eating rice prepared with Tamarind, on teak leaves”. As is well known, amongst the various consecrated food items dispensed to the faithful at the Tirupati temple in southern Andhra Pradesh, there is the pulihara/puliyodharai, or tamarind rice. The ubiquity of tamarind rice in South India is obvious. There is variation due to different kinds of rice used, the flavouring ingredients and quantities, and the spice heat. Telugu varieties, especially in coastal Andhra, are very spicy but at the very heart of the composite flavour resides the sour note. This sour, sacramental food is not just a temple staple; it is commonly made for family gatherings. Puli, the operative word here, in its semantic extensions, refers to not just the fruit and the plant, but also to sourness itself.

Amlarasa is the corresponding term for sourness and acidity in Ayurvedic texts. The oft-quoted phrase “amlam hridyanam” mentioned in the ancient treatise Caraka Samhita, is translated as “sour taste is pleasant to mind/heart.” The other term used for sourness in classical Sanskrit texts is cukra, which denotes several things—a kind of cane or sorrel, fermented grain or fruit vinegar, hog plum, or even tamarind, and the tamarind tree. Scholarly research indicates that it is not clear if the amla mentioned in classical literature is tamarind (as in Tamarindus indica), or some other souring agent such as kokam. In Amarakosha (an ancient Sanskrit thesaurus), there are references to tintidi, cinca and amlika and in other sources, kokam (Garcinia cambodjia or Garcinia indica), is known as tintidi, tintdik, and vriksha amla—names also used for tamarind. As one would expect, some of these names are found in regional languages across India. What is imli in Hindi, chincha in Marathi, huli or hunase-hannu in Kannada, puli in Tamil and Malayalam, is chinta in Telugu. The English name however, derives from the Arabic tamar-i-hind, or Indian Date.

Tamarind was possibly introduced to India via ancient maritime trade routes. Indigenous to the tropical Africa, it is interesting to note that the Senegalese capital city Dakar is named after the tree. The tamarind fruit, a durable food with abundant nutritional values, was carried by Arab and Ethiopian traders in its pulp form (tommar). Scholars have dated charcoal wood remains of tamarind at a site in Narhan on the banks of the Ghagra river, to the Chalcolithic period around 1300 BC. Its antiquity and provenance is yet another apt marker of the complex movement, settlement and intermingling of people over time.

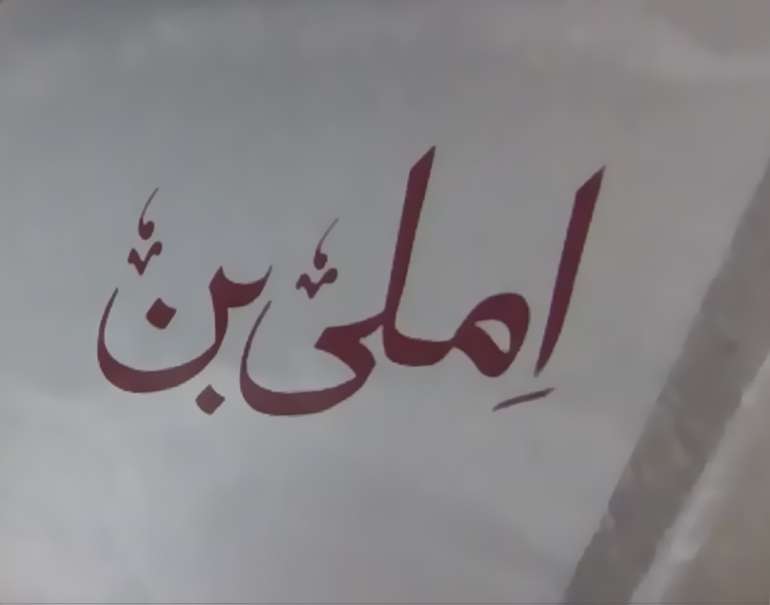

The Indo-Muslim encounter in the Deccan has resulted in exquisite art and architecture, and a glorious period of Dakhani literature. The golden period of the language for around 350 years lasted till Aurangzeb’s conquest of the region at the end of the 17th century, which saw a sweeping imperial Persianization of language and culture. Of the many interesting features of this mixed, shared history is food culture. Does the food of the Deccan correspond in some sense to the idiosyncratic and mellifluous intermingling of the linguistic influences of Dakhani, now a spoken vernacular? Some modern poets of the Deccan have artfully deployed this dominant note; whereas the late great Sarwar Danda’s published collected works bears the title “Imliban” (tamarind grove), the poet Aijaz Hussain, who migrated to Pakistan following partition, took as his pen name the appellation “Khatta”, perhaps signalling his general disposition and an affective proximity to the acerbic anti-hero—sourness. Indeed, in an true expression of the inscrutability of the Deccan and its people, who brandish their maverick and sometimes abrasive manners at will, Aijaz Hussain Khatta offers this telling couplet: Khattey ki laash khaddey mein nangi-ich gaad do; uske kafan ko ghair ki chaddar nakko-ich nakko (Bury Khatta’s corpse naked in its grave; no shroud of another will do, no-no.)

In an introduction to his wife Pratibha Karan’s book on Hyderabadi cuisine, the former Indian police officer and director of the Central Bureau of Investigation Vijay Karan, whose forbear Raja Sagar Mal migrated to the Deccan with Mir Qamaruddin Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I, the first Nizam of the province, says: “What also distinguished Hyderabadi food is its sourness, clearly a Telugu influence. No one else can sour his food like the Hyderabadi can.” This complexity and idiosyncrasy of the Deccani palate finds expression in a unique dish named Chigur ka Saalan, or Chigur Gosht. Mutton is cooked with the tender leaves and shoots of the tamarind tree. The young leaves are harvested in April and several preparations are made using it, including one with toor (arhar) dal. The use of sour greens with meat and pulses is common across the region; the aforementioned gongura (Roselle), known in Dakhani (and Marathi) as ambada is also widely used. The regional meal of “jowar ki roti, ambad ki bhaji” (Jowar, or Sorghum roti with sour green curry) is mentioned in Dakhani folk songs. The popular Hyderabadi dishes of Mirchi ka Saalan, Baghaara Baingan, and Tamatar Kut, stand testament to the enthusiastic adoption of tamarind in Deccan food traditions.

The apocryphal story of the invention of Sambar in the royal kitchens of the Maratha ruler Shahaji at Thanjavur to honour the presence of the founder of the Maratha Empire Shivaji’s son Sambhaji, points to the fondness for sour tasting foods. Interestingly, as the scholar Srinivas Sistla writes, the mention of Sambar and its ingredients, including tamarind of course, is found in the Vijayanagara king Krishna Deva Raya’s complex epic poem Amuktamalyada. Earlier still as he points out, there are references to tamarind and sourness in the poetry of the 15th century Telugu poet Srinatha, who was famous for his use of prabandha (versified narratives), and the Bhakti saint-poet Tallapaka Annamacharya. As Sistla reveals, a Telugu keertana (hymn) of the latter brings up the mix of sourness and sweet to refer to the delicate balance of man’s virtue and vice: “pulusu-teepu-nu-kalapi-bhujichi-natlu (“like mixing Pulusu and sweet to consume”).

The word sour (and sourness) is plagued by negative connotations, given that flavours and tastes are often linked with emotions. In many linguistic cultures, sourness is linked with jealousy and envy. Sour face, sour grapes, sour as vinegar, relationships gone sour, things ending on a sour note, leaving a sour taste in one’s mouth, sourpuss, etc—the many phrases and idioms in the English language that colour sourness (excuse the synaesthetic indulgence) with unpleasant shades are easily ignored in favour of the many delicious benefactions.

The evolutionary imperatives in the adoption of sour foods is quite interesting. Scientists speculate that early humans may have known that sour/acidic rotting fruit was safe to eat due to the action of lactic acid. The virtues of moderate ingestion of sour foods have long been known. Given its semi-arid, tropical climate, the Deccan plateau is perhaps an ideal home for tamarind (and sour fruits). Interestingly, recent studies seem to show the souring of Fuji apples due to climate change and global warming. Indian apple farmers also have been impacted.

Having grown up in a Telugu household in Hyderabad, my bias has remained intact. As a long-time Bombay resident I am now a lot more cautious in the use of pickles and pachadis but their conceptual dexterity, and taste, still gets me. There are of course many souring agents that are used in the Deccan—from kokum, lime/lemon, tomato, raw mango, vinegar, to dahi (yoghurt). There is also the intriguing use of the must of green grapes by some Irani families in Hyderabad. The range of sour foods too, is staggering—from Rayalseema’s Chepala Pulusu, western Deccan’s Sol Kadi, Tamil Vathal Kozambu, the Dappalam of the Krishna-Godavari belt, and the festive Injipuli of Kerala.

My own transcendental sour food experience is with the standard everyday home style dal known as pappu pulusu (sour dal). In one common variation, before the cooked dal (toor or moong) is finally added to finish the dish, in the watered tamarind pulp cooked on a slow flame with tempered spices and seasoning, several richly browned, partly blackened, small garlic pods fried in ghee are added. When this sauce cooks down slowly, the garlic pods release an intense pungent aroma and flavour. I’ve struggled to describe this flavour. The closest I have come, is to think of it as that luxurious opaque enveloping of flavour, smell, texture and sight that one experiences when a delirious fever of many days finally breaks. A heady flight from a liminal space back to the realm of senses. With some 1970s UK pop hits in the mix.

Sourness is the dude of flavours. And the dude, as we know, abides. For as the old Telugu saying goes: “Chinta chaccina, pulupu chavadu”, or, “the tamarind tree may die, but sourness never will.”

This is very impressive scholarship, & I have learned much. The range of pungent & sour foods in Southern India is distinctive, including preserved foods such as pickles, podis or ground chutneys or dals roasted together with tamarind & chilis & eaten with sesame oil or ghee, or several of the foods the author refers to above which can be eaten for days after preparation. Perhaps as a Tamilian with family connections in Andhra, Karnataka & Kerala, this familiar culture seems to me the richest. Yet is the employment of tart or acidic notes in South Indian cuisine unique? We know of vinegar in Goa, kokum down the West Coast & other sour plums elsewhere, as well as tamarind, lemon juice or tomatoes, amchur from sour mangoes in Northern India, just as pomegranate molasses are a part of some Arab cuisine, or yogurt, or sour berries in Iran; with rice, beans, lentils or meat.

I am so impressed with this writing and the whole approach to the topic. Such a learning.

What a presentation

A gourmet’s delight

Truly the taste of Pulihora reflected

What an amazing, analytical, scholarly and fun post! Many rasas indeed!

Entertaining and educational at the same time. Enjoyed this, thanks !

Really enjoyed reading this article! Not only does it make a compelling case in favor of sourness as the dude of flavors, but it also presents many interesting facts and nuggets of literature. As a Telugu man myself, I was delighted to be reminded of Annamacharya’s line “pulusu-teepu-nu-kalapi-bhujichi-natlu”. I’m off to make some “pappu-pulusu” for myself now!

A lovely ode to pulupu and the particular role it plays in Telugu cuisine! I would cook in college to try and recreate home food, since getting recipes from my mom was an exercise in futility, and I distinctly remember the inflection point when I realized that tamarind and pulupu played a much larger role than just appearing in chaaru, and all of a sudden, I could recreate the layered complex flavors I missed so much.

I thoroughly enjoyed and salivated through this piece, thank you. As a life-long believer in the sour elements in our food, this piece spoke to me <3 Beautiful!

Just discovered this article Gautam, and loved it! Enjoyed the mix of historical context, anecdotes, and your writing style. Nicely done 🙂